Gaming and Parents

Playing together: why so?

Videogames are everywhere. From the most complex (and costly) titles to an endless range of mobile games, simple apps that can be easily installed on smartphones. Gacha games, role-playing games, action-based games, MOBAs, MMORPGs, FPS, along with F2P and P2P. Acronyms and abbreviations that may seem meaningless at first glance—just random letters to those not "in the know"—yet behind them lie titles, commercial products, hundreds of thousands of jobs, and millions (yes, millions) of consumers of all ages and genders. What do these games have in common? They are entirely digital, accessible via smartphones, consoles (like PlayStation and Xbox), tablets, and computers. And so, in one way or another, they keep us engaged in front of a screen.

The latest report on the video game market in Italy (IIDEA, 2022) highlighted that in Italy alone, 15.5 million people—35% of the population between ages 6 and 64—played one or more video game titles, marking an increase of around 2.8% compared to the previous year. Certainly, the titles and especially the perception of what a videogame is and what it means to play it have changed. Contrary to expectations, as many adults play as young people or teenagers (no, gaming is not solely a teenage phenomenon; quite the opposite). However, preferences differ (but not the time spent in front of a screen!). If an adult, perhaps a senior, might prefer "simple" games and free apps, younger players may lean towards more "complex" commercial titles, playing either solo or with others, simultaneously and online.

Yet, despite the evidence and numbers that seem quite clear, discussions about digital games, families, and education often focus on the potential negative effects of gaming: it promotes antisocial behavior, encourages violence, leads to isolation, and distances children from their parents. But is this always the case? And, more importantly, is it so everywhere?

Not exactly! In several cultural traditions, such as the American one or those in what we consider “Nordic” or Scandinavian countries, family gaming is much more present and shared, likely due to a closer age range between parents and children (but not only this). The educational tradition in many Nordic countries (Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland...) often experiments with gaming, using and promoting it as an educational tool, and certainly does not demonize it in itself.

For this very reason, our project is also based on a partnership with Rafíþróttasamtök Íslands (RÍSÍ), an Icelandic eSports federation that has long been involved not only in tournaments, competitions, and athletes, but also in education and awareness on video gaming and digital addiction. This federation provides a space for young gamers who have turned their passion into a career, playing in teams in front of millions of spectators with the support of their families. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to see that here as well?

The Infinite Potential (and Infinite dangers) of Gaming

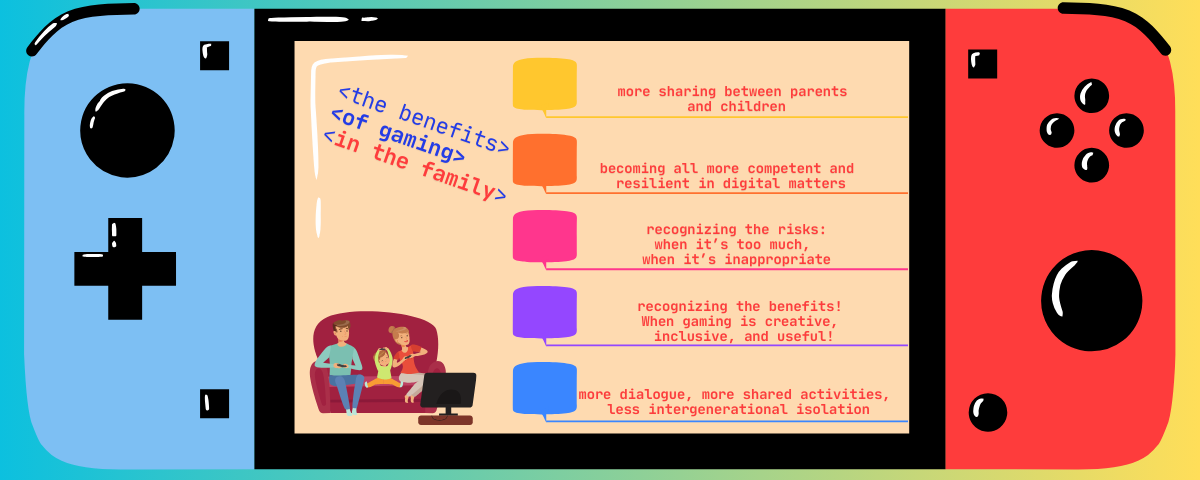

Like all things—from art to cooking, sports, or social activities (going out, being in a group, dancing)—gaming, understood as a simple consumption of cultural, audiovisual products, is not intrinsically good or bad. It all depends on how it’s used, on how this activity integrates into our habits and daily life. Much like sports, gaming can become a compulsive activity and can indeed lead to isolation (a different matter is aggression: studies now largely debunk the idea that gaming can lead to violent behavior). What’s true, however, is that video games are here to stay, if anything, expanding. The market is steadily growing and now drives the entire global audiovisual industry (far more than cinema or TV series!). So, given the circumstances, wouldn’t it be better for a parent, rather than dismissing this activity entirely (and likewise, before approving it without reflection, simply handing over a tablet or computer), to learn more about it? Wouldn’t it, in the long run, be preferable to be able to mediate video game consumption, integrating it in a healthy way into family habits?

If gaming can indeed be dangerous, wouldn’t it be better to truly understand its risks without falling into stereotypes or preconceptions? To know when it’s too much, when a game is suitable for a particular age group and when it’s not (and, importantly, why—not simply reading the label), to understand, based on personal interests, which activities or titles might suit one’s family unit and which might not.

At the same time, if it’s true (as the entire industry literature now supports) that video game consumption can serve as an educational tool with significant potential, stimulating players interactively and influencing concentration, creativity, memory, logic, language learning, and teamwork, wouldn’t it be preferable to have the skills to navigate and enter this world even slightly more consciously? More than focusing on whether gaming is or can be inherently right or wrong, the real difference lies in parental competence: many parents, being gamers themselves, have the advantage of fully understanding what their children are doing and why, and can even share gaming activities with them, together appreciating the positive, educational, and formative aspects of gaming.

However, many other parents are unfamiliar with these digital products, entirely reject them, or worse, leave their children to figure it out alone. That’s when gaming could indeed become isolating and, primarily, something done in solitude, a true suspension of family time.

Activities and Outcomes

Gaming and Parents, Close in the Distance, and RÍSÍ aim to:

-Develop a concise handbook in Italian, English, and Icelandic for parents—a true guide to the world of video gaming and integrating it within the family. This resource will focus particularly on digital parental mediation: how to be an engaged parent in digital activities, understanding what happens on screen, recognizing the positive aspects as well as potential negative impacts (and, in such cases, knowing what to do and where to seek help if necessary).

-Implement a support course for parenting, available both in-person and online, spanning Iceland (and Scandinavia more broadly) and Italy, free and accessible to all interested parents.

-Create "e-libraries" on partnership websites: online libraries and archives on family-oriented video gaming and digital parental mediation, useful for new parents as well as stakeholders and other organizations such as parenting support centers, organizations addressing new dependencies, and more.

-Host awareness events and a training exchange program for Close in the Distance team members in Iceland, aimed at learning from RÍSÍ's working methods, the eSports sector, and Scandinavian digital culture.

...And finally, there will be EPALE entries and various dissemination products.

For more information, visit our Instagram page, EPALE, or our Blog section!

Or write to us at: direttivo@closeinthedistance.com

Gaming and Parents, sometimes also referred to as "High Rollers!" is the acronym for "Gaming and Parents: Education in Game Media Literacy and Digital Parental Mediation."

Its project code is 2023-2-IT02-KA210-ADU-000175959.

Co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Commission, it is an Erasmus+ KA210 project (Small-Scale Partnerships) within the Adult Education sector, which began on February 1, 2024. The project will conclude on January 31, 2026.

For this project, Close in the Distance and Rafíþróttasamtök Íslands received EUR 48,000.00, equivalent to 80% of the total co-funding, from the Italian National Erasmus+ Agency I.N.D.I.R.E.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.